Campaign Finance

Follow the Money

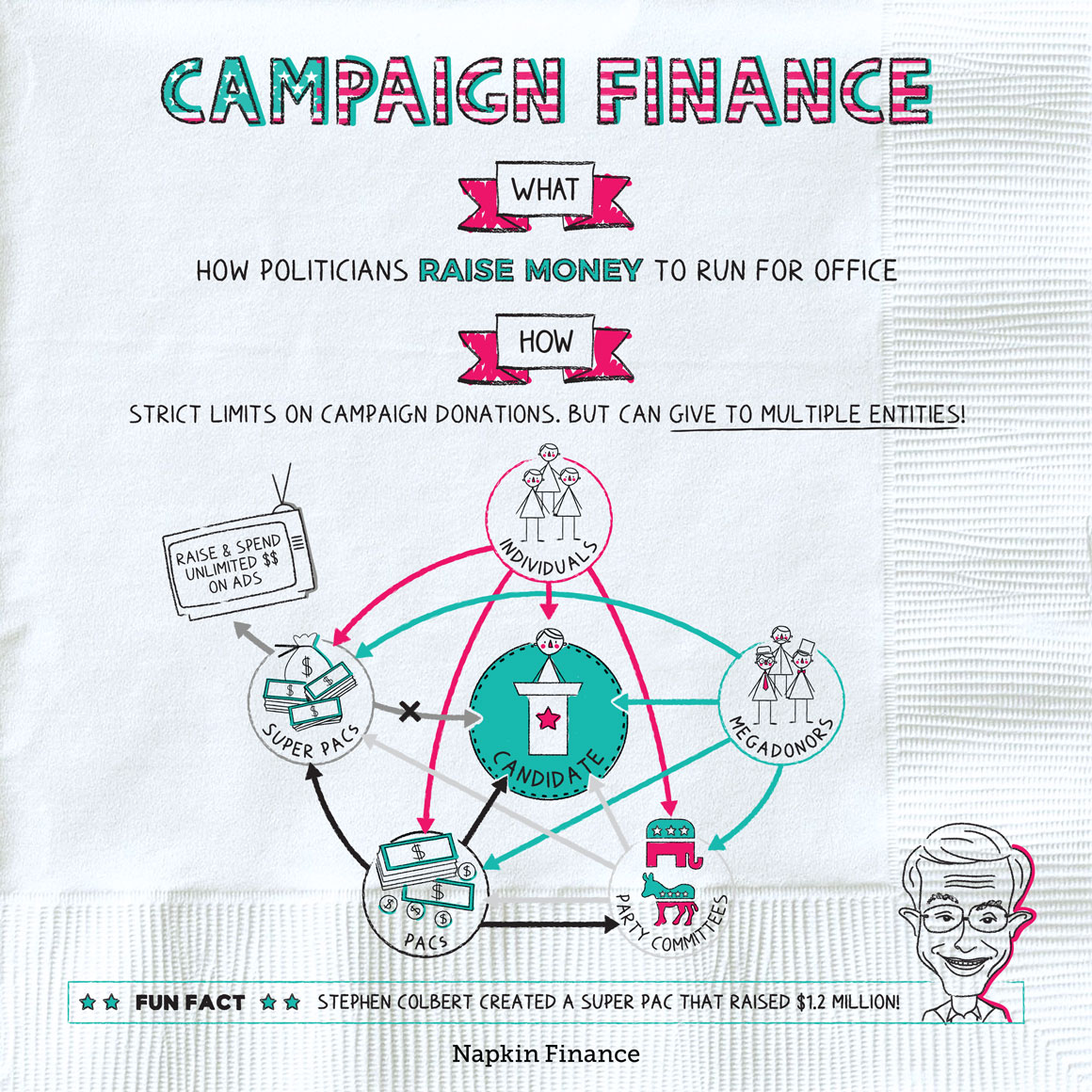

Campaign finance describes the way political candidates raise and spend money to run for office.

Running for election can be expensive. Candidates may need to pay for:

- Staff—such as a campaign manager, an advertising team, website designers, and organizers to coordinate volunteers.

- Office space for their campaigns—some candidates may need only a small headquarters in their hometown, while others may also need local offices throughout their state or the country.

- Advertising—it costs money to buy TV ads or billboards.

- Research—candidates may need to research their opponent or do polling to find out how voters respond to their ideas.

- Travel—to win the Iowa caucus, you probably have to travel to Iowa, and that costs money.

- Events—candidates may need to host rallies, dinners, or meet-and-greets with voters.

Candidates for local office may be able to fund their campaign entirely with their own savings or with only some small contributions from family and friends.

When it comes to national politics, however—and particularly running for president—candidates typically tap a range of funding sources:

| Who | What | How much |

| Individuals | Normal people like you. |

|

| Megadonors | Wealthy people who want to influence policy or be close to the action. |

|

| Party committees | Think the Democratic or Republican National Committees or a particular state’s equivalent committee. |

|

| Political Action Committees (PACs) | Typically represent a particular industry or interest group, such as banks, unions, or gun owners. |

|

| Super PACs | A special type of PAC that doesn’t make any contributions directly to campaigns. |

|

Those limits may sound pretty small next to the roughly $500 million to $1 billion it can take to run for president. Here’s how individuals, corporations, and other groups are able to boost their impact:

- They give to multiple entities

- One person or corporation can give to a candidate’s campaign, the national party committee, various state-level party committees, and an assortment of PACs to increase their total contribution.

- Those entities can funnel their money to one another

- A state’s Democratic or Republican committee can send all the funds it receives to the national party. And the national committees can send money back to the state committees.

- A PAC can give to a party committee or to another PAC and vice versa.

- They make “independent expenditures”

-

- If you decide to go out and buy advertising slots for your favorite candidate, there’s no limit on how much you can spend, as long as you don’t coordinate with the candidate’s campaign.

- Super PACs exclusively use this type of spending.

Many experts believe the U.S. system should be reformed because it can create a cycle of influence. Here’s a simple example:

Corporation A wants less restrictive

laws on pollution.

↓

Corporation A gives a large sum of money

to a Super PAC supporting Candidate X.

↓

Because Candidate X received so much

financial support, he or she wins the election.

↓

Candidate X wants Corporation A’s support

in the next election, too, so he or she tries to get

looser pollution laws passed.

That cycle is problematic because the U.S. is a democracy, so the government is supposed to work for the people—not for corporations or industries—and not only for the wealthy.

Some of the fixes that have been proposed for the U.S. system include:

| What | How | Pros | Cons |

| Public funding | Candidates only receive and spend government money. | Gets corporate money out of politics. | Relies on tax dollars. |

| Public matching | Government matches small donations a candidate receives from individuals. | Boosts the influence of individual Americans. Reduces influence of corporate money. | Still relies on tax dollars. |

| Shorter election cycles | Pass laws that change the election calendar and/or limit when candidates can start campaigning. | A two-month election cycle would cost less than a two-year cycle, so candidates wouldn’t have to raise such huge sums. | Voters wouldn’t have as long to get to know the candidates. |

Some states and localities already use a version of public funding. Presidential candidates can choose to use public funds, but doing so strictly limits how much they can spend in total—so few ever do.

It’s not legal to buy votes, but it is legal to spend huge amounts of money trying to convince people to vote a certain way. Although many people agree that the current U.S. system is problematic, there’s little agreement on exactly how to fix it.

- About $6.5 billion was spent on the presidential election and congressional races in 2016.

- The largest PAC contributor during the 2017-18 election cycle was the National Beer Wholesalers Association, which contributed more than $3.4 million to candidates—48% of that to Democrats and 52% to Republicans.

- Industry groups and corporations often contribute to both parties so that no matter which side wins they have some influence.

- Campaign finance describes how candidates and political parties raise and spend money to try to win elections.

- Major sources of funding can include small donations from ordinary individuals and large contributions from wealthy people, corporations, and groups that represent certain industries or interests.

- Although there are strict limits on how much anyone can donate to a candidate’s official campaign war chest, donors can effectively give unlimited amounts by contributing to other entities.

- The U.S. system is controversial and problematic, but there’s no broad agreement on the best way to fix it.