GDP

Grossly Underrated

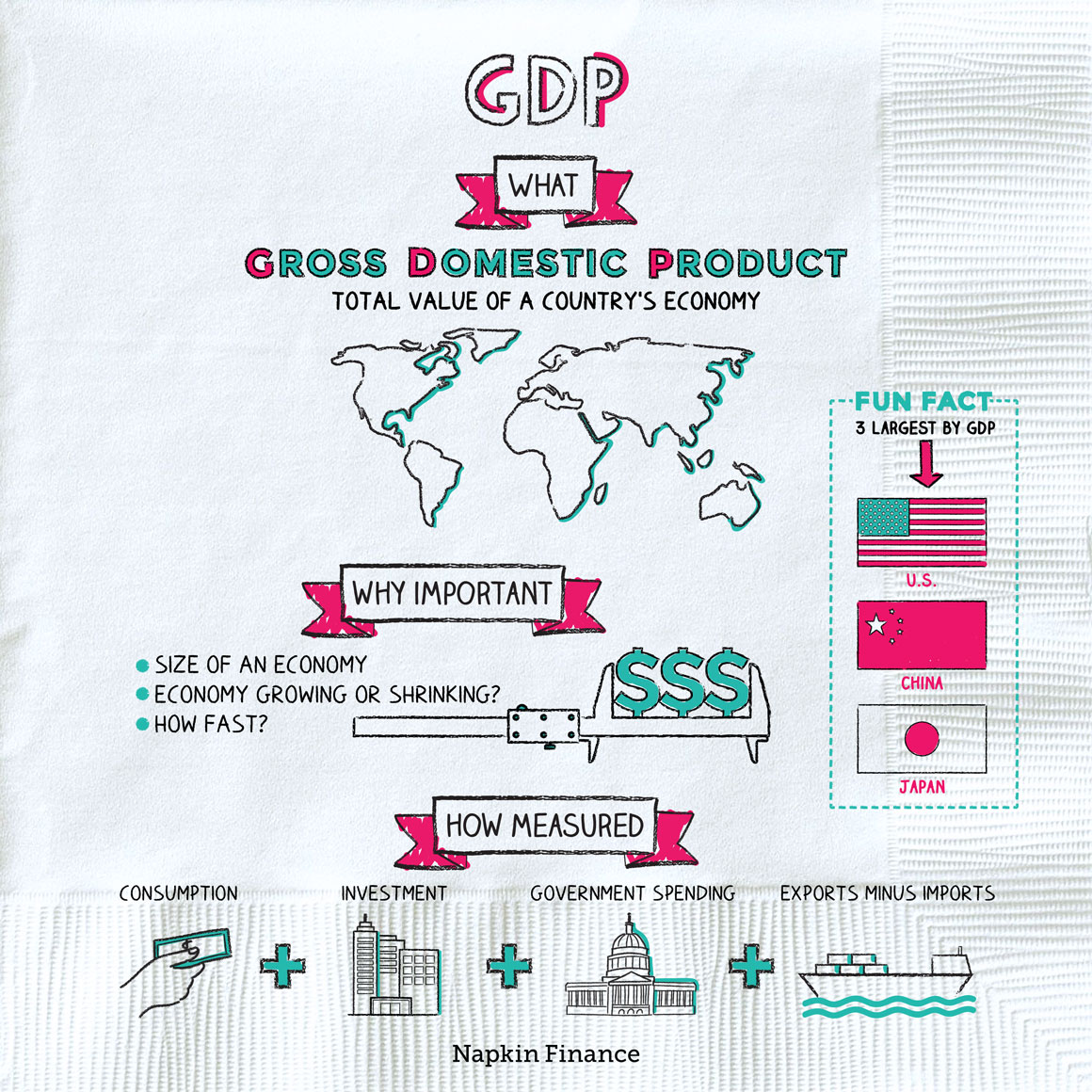

Gross domestic product, or GDP, measures the size of an economy. In essence, it puts a dollar figure on all the goods and services that a country produces in a given year (or other period).

Tracking a country’s GDP tells us two things:

- The overall size of the country’s economy

- Whether the economy is growing or shrinking and at what rate

Investors, governments, and others watch GDP closely because it’s generally considered the single best measure of how an economy is doing.

In normal times, GDP should be increasing at a steady pace (that’s called an expansion), workers are generally able to find jobs, corporations are turning profits, and, typically, stocks are rising.

The opposite state of affairs is when the economy shrinks—called a recession. That can mean workers are losing their jobs and corporations are losing money. If unchecked, recessions can turn into economic death spirals (see: the Great Depression). Governments may watch GDP closely for any clues the economy could be headed for a recession so that it can take steps to try to avoid or soften one.

GDP includes four basic components:

- Consumption—Just about everything you (and others) buy, such as a new car, a sweater, or a bag of groceries, gets added to GDP.

- Investment—This includes when a company builds a new factory or a homebuilder builds a new block of condos.

- Government spending—This category includes everything from federal government spending on the military to a local government repaving a road.

- Exports and imports—If the country ships more goods and services abroad than it imports, this component is added to GDP. If the country imports more than it exports (called a trade deficit), then the difference is subtracted from GDP.

GDP has many different uses:

- Governments consider it when setting financial policies and spending levels

- Companies may use it to decide whether to set up shop in a certain country or area

- Investors use it to decide where to invest their money

- Economists use it to measure productivity and prosperity, track how fast an economy is growing (or shrinking), and compare economies to each other

“While GDP and the rest of the national income accounts may seem to be arcane concepts, they are truly among the great inventions of the twentieth century.“

—Paul A. Samuelson

GDP at a specific moment in time doesn’t always paint a full picture of economic strength. Economists instead look at GDP growth (the difference in GDP year-to-year or quarter-to-quarter) over time to see how an economy has performed and project what it might do in the future.

GDP growth (%) = (GDP this period – GDP last period)

———————————————

GDP last period

The percentage can be either positive (indicating growth) or negative (indicating contraction). Two or more quarters of negative growth in a row indicate a recession. A depression is a downturn sustained for a few years.

GDP is a measure of an economy’s health. Economists, investors, governments, and others around the globe use it to compare countries to each other, set spending policies, and decide where to invest.

- At about $20 trillion, the U.S. is the world’s largest economy followed by China and Japan.

- If California were a country, it would rank as the fifth largest economy in the world—ahead of the U.K., India, and France.

- GDP only includes over-the-table transactions. That means the illegal drug trade, prostitution, and your neighbor’s under-the-table nanny’s pay don’t get counted.

- GDP measures the size of an economy.

- Investors watch GDP closely for signals as to how the economy is doing.

- GDP includes goods and services that individuals, corporations, and the government buy but doesn’t include black market or under-the-table activity.

- GDP has a range of uses, such as helping a government decide how much it should spend or an investor determine the best places to put money.

- Instead of looking at a single GDP figure, investors and others typically follow GDP growth, which shows how an economy performs over time.