Lesson 2: Types of Accounts

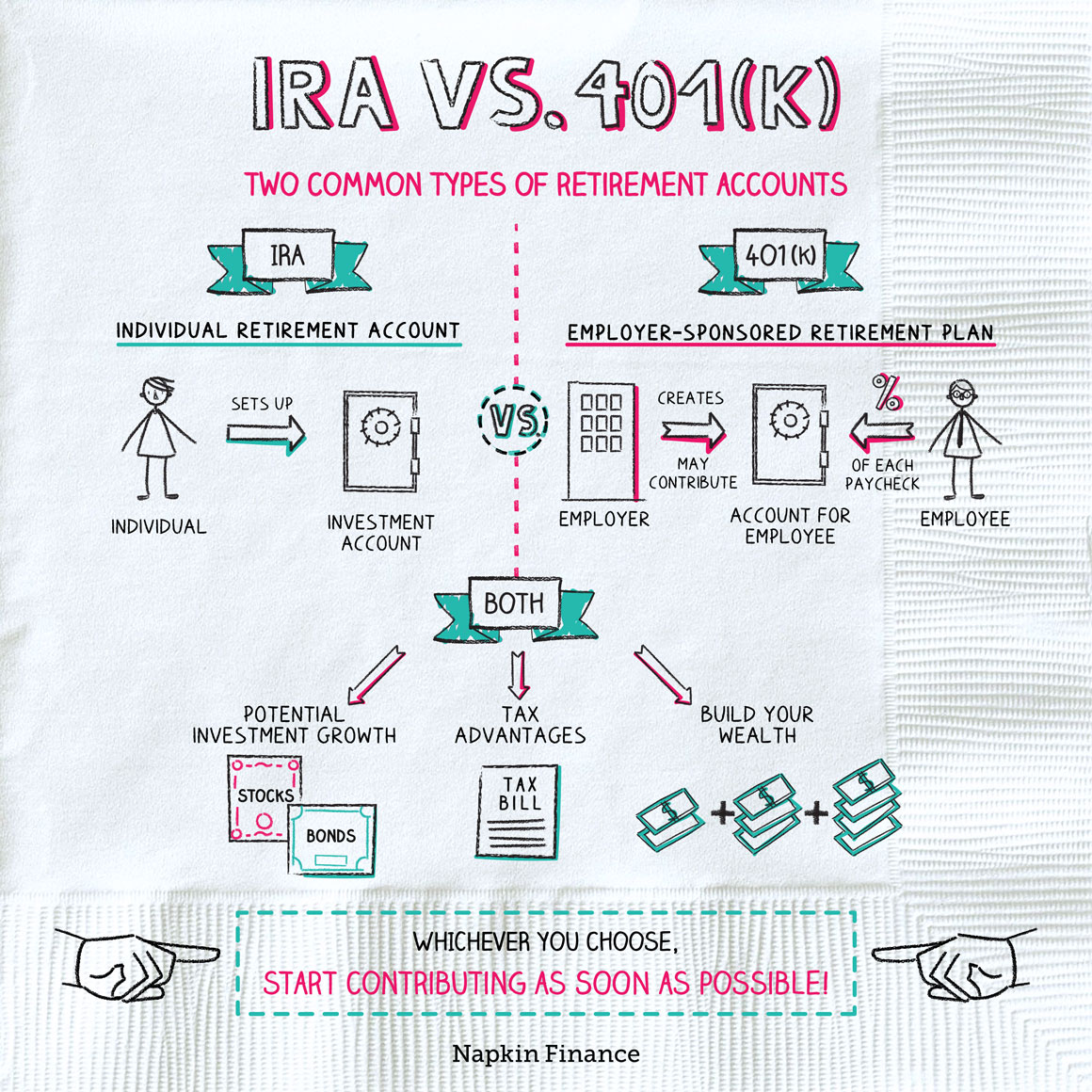

Once you’re ready to start saving, you need to choose a dedicated retirement account to put your money into.

The world of retirement accounts can feel intimidating at first, with its alphabet soup of acronyms. But try not to get overwhelmed. Chances are you’ll only ever need one or two of the more common account types.

Why important

Although you could simply save in a savings account or in the type of ordinary brokerage account investors use to hold stocks and bonds, you’ll almost certainly be much better off using a dedicated retirement account.

That’s because retirement accounts qualify for special tax perks, which let you avoid paying taxes on your money’s growth while it’s in the account. (By contrast, the interest you earn in a savings account and the growth on your investments in a brokerage account are taxable when you earn or realize them.) Over time, skipping all those tax bills can really add up.

Employer-sponsored vs. individual accounts

Some types of retirement accounts are set up by employers and offered to employees as a benefit. Others you set up on your own with a financial institution (such as an online broker). Here’s what that distinction means:

| Employer-sponsored | Individual | |

| Examples |

|

|

| How to open an account | Through HR (if your employer offers one) | With a financial institution, such as a broker or bank |

| What investments are available? | A limited menu of investments that your employer has decided to include in the plan | A broad menu—typically, whatever investments the institution offers |

| Main benefit | Free money. Employers often match your contributions up to a certain amount. | Flexibility and control because you’re completely in charge of your account. |

Tax-deferred vs. tax-free accounts

Another way of making sense of the various account types is by considering which ones are tax deferred (meaning you’ll have to pay taxes when you start withdrawing money from the account—as if that money were a paycheck) versus tax free (meaning you already paid taxes on that money, and you won’t have to ever again).

Here’s how that difference breaks down:

| Tax-deferred | Tax-free | |

| Examples |

|

|

| You contribute | Pretax dollars (either through payroll or by taking a deduction for your contributions) | After-tax dollars |

| Owe taxes on withdrawals? | Yes. Withdrawals taxed as income (like a salary). | No. Withdrawals in retirement are tax free. |

Where to start

Chances are you don’t need to evaluate every single account type. If you’re picking or rethinking a main retirement account to use, here is some basic guidance to get you started:

| If you are… | Then consider… |

| An employee and your employer sponsors a plan | Your employer’s plan |

| An employee and your employer doesn’t sponsor a plan | A traditional IRA or Roth IRA |

| Self-employed (i.e., a contractor or small-business owner) with modest earnings | A traditional IRA or Roth IRA |

| Self-employed (i.e., a contractor or small-business owner) with higher earnings | A SEP IRA or solo 401(k) |

| A stay-at-home parent | A spousal IRA |

Good to know

There are two major downsides to saving in dedicated retirement accounts. One is that there are rules limiting how much you can save in any of these accounts in a given year—and you have to learn and stick to those limits.

The other is that they come with restrictions on when you can withdraw money. Generally, withdrawing money before age 59½ may mean you have to pay some special penalties to the IRS (though there are some exceptions, and Roth IRAs in particular have looser rules on withdrawals).

That means you should only use the accounts for money that you truly intend to set aside for retirement. Your emergency fund, your wedding planning fund, or funds for any other big goals should live in different accounts.